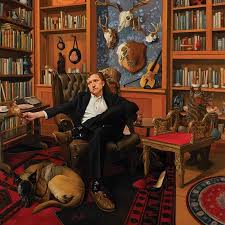

TYLER CHILDERS : SNIPE HUNTER

- Eatin' Big Time

- Cuttin’ Teeth

- Oneida

- Getting to the Bottom

- Bitin’ List

- Nose On The Grindstone

- Watch Out

- Down Under

- Poachers

- Snipe Hunt

- Tirtha Yatra

- Tomcat And A Dandy

- Dirty Ought Trill

Label : Hickman Holler Records

Release Date : July 25, 2025

Length : 53:53

Review (Pitchfork) : It is certainly a surprise to hear Tyler Childers fantasize about making a pilgrimage to Kurukshetra—an Indian city north of Delhi where the Mahabharata was set—but it is not a shock. While he may be the first person with a Kentucky drawl to sing about dharma, rolling “like the Pandavas” with his brothers, and bringing his wife and mother to a nirvana-like oasis where they sing Hare Krishna and West Virginia fiddle standards alike, it is, somehow, not completely out of the way for one of country music’s most singular artists. Ever since Purgatory, his now-classic 2017 album, turned him into a star Appalachia could call their own, Childers has made it his mission to redefine what that means. Yes, his father worked in the coal industry. Yes, he grew up in a trailer that sat next to a Baptist church. And yes, he plays a fiddle as if he’s soundtracking bootleggers in a wagon race. But he also was one of the few country stars to speak up in support of Black Lives Matter in 2020. Two years later, he made a gospel record that preached interfaith harmony, and more recently, he became the first country artist on a major label to release a music video that features a gay love story. For years, Childers has dealt in statements and had his “legitimacy” as a country musician pinballed by press and fans. His music has never been co-opted by outside noise, but his releases have been neatly packaged and limited in scope. Long Violent History is strictly a fiddle record; Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven? is his take on gospel; Rustin’ in the Rain channels Elvis. On Snipe Hunter, however, he lets everything hang in the wind, blending vintage ballads, rockabilly, and psychedelia with renewed artistic freedom. It’s his most free-spirited and pleasantly weird album to date. Perhaps it was the magic touch of producer Rick Rubin or the tranquility of recording in Hawaii and Malibu that allowed Childers to drop his shoulders. Regardless, Snipe Hunter reveals his quirks while staying true to the traditions that made him. There is a Southern-rock ripper that sounds like an oncoming panic attack (“Snipe Hunt”), a ragtime stomp about the person Childers would bite first if he had rabies (“Bitin’ List”), and a pair of tracks on the back end (“Tirtha Yarti,” “Tomcat and a Dandy”) that play on his admiration of Hinduism, even interpolating a Hare Krishna chant in the style of a 19th-century battle hymn. (In a GQ interview, Childers described a recent trip to India, where he became acquainted with “Krishna devotees” whose practice gave him “just as much strength and guidance as his Christian upbringing.”) Even with these more experimental elements, this is still a Tyler Childers album, rooted in vulnerable songwriting and tonal grit. Take “Eatin’ Big Time,” where he scowls like a mad, gluttonous king and gives a gruesome account of gutting prey, eventually demanding to know if his audience has ever had the chance “to hold and blow a thousand fucking dollars?!” This chaotic, semi-ironic opener leads into “Cuttin’ Teeth,” a serene, pedal steel-led tune about the early days of a country singer, presumably Childers, who lives gig-to-gig with a “bunch of West Virginia deadbeats.” He sounds wistful, as if things were a whole lot simpler back then. The most poignant tracks are two singles, “Oneida” and “Nose on the Grindstone,” known to fans from previously released live versions. Both originate in Childers’ Purgatory era, a period defined by hunger and heartache, and follow the stripped-down, “three chords and the truth” recipe that shot him to fame. The polished, Rubin-produced studio versions simultaneously recall Childers’ initial flame and mark its evolution—an evolution realized in the richly layered arrangement of “Getting to the Bottom,” where he celebrates his nearly six years of sobriety by wondering just how hammered his old drinking buddies are right now. As intentional and disciplined as Childers’ releases have been, it’s refreshing to hear him make an album without an agenda or a rulebook. Through the detours into Australian ecology and the cheeky mispronunciations of Sanskrit words, he’s still what everyone says he is: an Appalachian man with a penchant for storytelling. Snipe Hunter is his first record to capture and celebrate the depth behind that.

Review (Saving Country Music) : It’s nowhere near as good as some of the hyperbolic proclamations being bandied about profess, and it’s not even close to the colossal letdown that others are alleging. It’s an album that finds Tyler Childers finally gracing fans with actual new, unheard material, showing off his knack for taking bumpkin-isms and making both hilarious and meaningful moments from them … and then Rick Rubin misunderstanding this material, and scuttling what otherwise would have been a pretty solid album, and still is in moments. The Snipe Hunter starts off strong with an impassioned though tongue-in-cheek track called “Eatin’ Big Time” that captures Childers somewhat sarcastically bragging about his Gold and Platinum records and $1,000 watch. “Eatin’ big time” was like an inside joke between Childers and his entourage back when he still haunted social media. It underscores how Tyler is sometimes at his best when he can work his deadpan humor into the equation. But as you go into the second song “Cuttin’ Teeth,” you immediately pick up on one of the biggest foibles of this record. Tyler Childers sounds like seven different singers during this 13-song album, with Rick Rubin either allowing or encouraging Childers to go places vocally that are unflattering. Along with all the other assets you can praise Childers for, he’s an incredible singer. The pain he brings, and the inflections that comes across so naturally to his tone is what has made Childers such an intriguing artist. But whether it’s getting him to sing in unusual keys, running his vocal signal through unnecessary filters, or tasking him to scream out stanzas under some misguided notion this creates an emotive experience, the times that Tyler Childers actually sounds like Tyler Childers on this album are fleeting, and come most obviously in the two songs released early from the album, and the ones we already had previous versions of: “Oneida” and “Nose On The Grindstone.” This same questionable approach of being experimental for experimental’s sake besets multiple songs on the album when it comes to production, arrangement, and music, especially in the second half. Some have claimed this is an album that’s more intentionally indie rock, and folks shouldn’t criticize it just because it’s not country. But most of the songs themselves are actually the folk-based Appalachian country Childers is known for. It’s the production that feels out of place, not audience expectations. And though it’s easy to offer up Rick Rubin as the sacrificial cow for Snipe Hunter‘s weaker moments, if we’re being honest, some of Tyler’s new songs are somewhat weak as well. “Bitin’ List” is a silly song, but just like “Eatin’ Big Time,” it shows off the endearing humor of Tyler’s personality. However, “Down Under” is just a dumb song that sounds like it was written from boredom on a plane back home from an Australian tour. You allow for one or two silly songs from Childers. But Snipe Hunter has one or two too many. Yet those that can’t find a reason to praise the album’s strong moments are selling themselves short. If we’d never heard “Oneida” and especially “Nose To The Grindstone” before, we would be lauding them as two of Tyler’s finest, because they are. It’s not this album’s fault other version have been worn out previously. “Getting To The Bottom” is a good song, even if it’s a key too low for Tyler’s vocal sweet spot. “Watch Out” and “Poachers” are solid tracks as well, and ones you look forward to seeing live. There’s nothing political about this album at all, but “Tirtha Yatra” is certain religious, with Childers using the song to recall his exploration of Hinduism, even if it’s in done in his folksy, Appalachian attitude. The next song “Tomcat and a Dandy” is very Appalachian, but with “Hare Krishna” chants in the background, pulling it into the domain of the religious as well. Tyler Childers should be allowed to explore his spirituality through his music, and both “Tirtha Yatra” and “Tomcat and a Dandy” are well-written Tyler Childers-style songs. It’s just the production once again that sours the experience. Both of these songs served more straight would have resulted in a much more entertaining and sustainable listening experience. The final song “Dirty Ought Trill” that should have been the “Whitehouse Road” of this record, meaning song exploiting the best of Tyler’s knack for building characters and bringing them alive with Appalachian vernacular. But the track’s turned into some pseudo hip-hop thing that ultimately becomes one of the primary culprits for people registering their strong disappointment with this record since it’s the last thing they hear. And just like on the first song on the album, there’s unusual overcussing that doesn’t work toward emphasis, but comes across more like a 12-year-old just learning to swear. With the strong and fresh material that Tyler Childers brought to this project, Snipe Hunter could have been a retrenching, revitalizing album for his career that overall has been coasting off the strength of the now 8 year old Purgatory. It could have been what Weathervanes was to Jason Isbell, or The Price of Admission is to the Turnpike Troubadours. Instead, there’s too much weirdness misunderstood as creativity or “boundary pushing” to resonate deeply. For all we know, Rick Rubin is the brilliant producer he gets credit for. But he doesn’t know his way around Appalachian folk music. That’s made clear by the results of Snipe Hunter. If Rick Rubin did anyone a favor, it was Cody Jinks who released his new album In My Blood the same day. The contrast between the Cody Jinks album really makes a strong case for artists sticking to what they do best as opposed to wild experimentation under a misguided notion of exploring creativity. Tyler Childers chose to work with Rick Rubin, and made a purposeful effort to include more original material on this new album under the correct notion that what he’d done one his last few releases wasn’t working, or at least as good as it could be. But it’s fair to assess that when it comes to making albums, Childers is still searching for his compass point after parting with Sturgill Simpson as producer. Nonetheless, this album benefits from subsequent listens. Since it intentionally challenges the listener, and makes such wild mood swings in approach, giving some time for the strength of the written material and some of the better tracks to reveal themselves is strongly advised. This is not a bad album. No matter your tastes, most anyone can cherry pick their way through it and find some good stuff. So why are we seeing such a strong negative reaction to Snipe Hunter, even more so than some of the questionable production deserves? It’s the same reason some are calling it the best album of the year, even though it’s still July. Often when you have a big release like this, there is one select, “exclusive” feature released. In this case it was a puff piece by Marissa R. Moss in GQ. “He’s an arena-filling Nashville outsider who wrote a Black Lives Matter anthem and put a gay love story in a music video,” the subheading proclaims. “Now, fresh off a pilgrimage to India, he’s releasing his spiritual and artistic opus, Snipe Hunter. ‘If I’m trying to talk to another young Tyler out there, he needs to know he’s not going to hell for thinking something else different.'” Most importantly though, a portion of the feature where Childers proclaimed his no longer plays his Double Platinum Certified song “Feathered Indians” due to the potentially offensive nature of the term “Indian” was turned into a viral meme by major social media outlets like Country Central, Country Chord, and Whiskey Riff. This created a “woke” poison pill for the record on the eve of its release, and soured the well of sentiment for many country fans, and for a record that otherwise has no political statements, aside from perhaps some mild and subtle ones. Meanwhile, in the type of ultra elite circles a publication like GQ caters to, they’re taking this record as something you must support strictly for political purposes. Just like Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter, you’re supposed to praise Snipe Hunter to the hilt as an action of moral preening. The title of the feature is “How Tyler Childers Made the Most Visionary Country Album of the Year,” as if this is possible to declare in July, from an outlet that most ignores country, and by an author who abhors its fans. But both politically-motivated takes on Snipe Hunter are irrational, just like much of political thought in 2025. Tyler Childers presents some great songs on Snipe Hunter. Rick Rubin presents some misguided decision making. This all results in a mixed bag that no matter your tastes or ideologies, leaves you with a feeling like once again, Tyler Childers leaves himself short of what he’s able to achieve if the stars are aligned, with his 2023 album Rustin’ In The Rain probably the superior project, if for no other reason than it was more consistently emblematic of Tyler Childers, despite the lack of more new, original material. Some songs of Snipe Hunter remain brilliant works of Appalachia country. But when rock production is brought to them, they’re pushed into the domain of “Americana,” meaning an amalgam of American music influences. As Tyler Childers once said himself, “Americana ain’t no part of nothin,” and unfortunately, that’s what certain moments feel like on Snipe Hunter.

Review (Americana Highways) : For some artists, a mega-successful debut becomes an unanticipated obstacle. Often, it’s not the subsequent music that fails to any degree – rather, that one album hits such a spot, at just the right moment, for so many listeners that it’s impossible to hit that mark again (Pearl Jam’s Ten has always been that album for me – maybe they have “better” albums, but I’ll never again be in that place and time again where that particular band will explode into my ears and change the way I listen). Tyler Childers seems to be living a version of that dilemma. His full-length debut, 2017’s Purgatory (has it only been eight years?) was a monumental record for left-of-center country listeners. And that post-release cycle was, for him, quite turbulent – remember his “acceptance” of the 2018 Americana Award for Emerging Artist: “I feel Americana ain’t no part of nothin.’” Fame and adoration weren’t really what Childers was after. They still aren’t. And that, for the most part, is good – he’s never, quite honestly, given a damn about pleasing or pandering to anyone. Whether it was the fiddle-driven Long Violent History, released in late 2020 with a title track that upset the “shut up and play portion” of his crowd, or the video for 2023’s “In Your Love,” which featured a love story between two (male) coalminers, he’s never felt the need to placate his “base” – he makes the music he wants to make. Which makes his latest album, Snipe Hunter, a stick in the eye of the Nashville posers who are the reason that we’ve been hesitant to label Childers as a “country” artist – he’s doing something entirely different than the denizens of Music Row. A few years back, Childers famously explained why he refused to move to Nashville – essentially, because that’s not where the stories are. The Kentucky native stays true to his raisin’ by telling the tales of the types of people he grew up around. The thing is, there are only so many stories that can come out of hunting, small-time drug running and other hardscrabble ways to make a living, so Childers had to come at these topics from different angles. Snipe Hunter begins with a huntin’ song, although an admittedly funky one. “Eatin’ Big Time” is all rifle scopes, deer blinds and exsanguination, set against Matt Rowland’s riotous organ, but with more than a little braggadocio mixed in – “Keep my time on my Weiss/Ya goddamn right I’m flexing/’Cause a thousand dollar watch is fine enough flex for me.” “Cuttin’ Teeth” is a western swing-ish call-out of an (unnamed) musician formerly, briefly, in Childers’ orbit – “Fronting him a country band/Roaddoggin’ in a stripped out van/Bummin’ powder in the barlight” – before moving onto bigger (but most definitely not better) things. In a glossy Nashville-driven world where “feat.” might be the most important verb in a press release, the only big-name guest on Snipe Hunter is producer Rick Rubin. And even though Rubin’s guru-like footprint has kicked the sounds of everyone from Tom Petty to Slayer to new places (and sales levels), his main role here seems to be delivering the noisiness (in a good way) of Childers’ long-time band, The Food Stamps, from stage to record. From the Zeppelin-ish intro of “Watch Out” to the uptempo indie feel of “Down Under,” this (like Childers’ live shows) is a balls-out rock experience. Even one of the two “old” Tyler songs featured, “Nose on the Grindstone” (receiving its first-ever studio treatment), adds a swirly organ crescendo to Childers’ acoustic picking. But subtlety has a place, as well. “Tirtha Yatra,” one of the few songs here to venture outside the holler (the title reflects a pilgrimage to connect with God), could have gone all India-cliche, but Kory Caudill relies on a number of more traditional keyboards (and a really cool Wurlitzer solo) to set the mood, relying on Childers’ words – “But comin’ from a cousin lovin’ clubfoot somethin’ somethin’/Backwood searcher I would hope that you’d admire the try” – to paint that picture of a self-confessed hillbilly venturing out to try something new (note – between this and “Down Under”’s images of pugilistic kangaroos and syphilitic koalas, I’d love to hear more about Tyler’s travels on a future record). The central point, though, of either Snipe Hunter or an actual snipe hunt is to lure an unsuspecting rube into exposing his own ignorance. The early-on fans who subsequently dismissed Childers for, among other “sins,” getting sober (as if their musical enjoyment is more important than the man’s health), might be enticed by tunes like “Tomcat and a Dandy,” where they could see the singer missing his wilder days – “In the fledglin’ of my prime/Back when I blew through all my time.” Really, though, those “dandy” ways – and those not-so-careful listeners – are something that Childers is fine to leave behind while closing his circle to a few essential people – “When the curtain falls on the part I play/Too soon for the ones that know’d me” – even as the more fickle chunk of his fan base ebbs and flows. In the meantime, as Childers relays in “Snipe Hunt,” we’re all stuck trying to separate the real from the bullshit, the next hot thing from the truth – “That’s the way I feel when I look at our past/And the handshakes that you gave me if you’re callin’ them that.” At times, life, for all of us, is a snipe hunt. Song I Can’t Wait to Hear Live: “Tomcat and a Dandy” – Childers’ gorgeously scratchy fiddle, along with Matt Rowland’s accordion and Nick Sanborn’s pump organ, create just the right amount of sonic gauze to layer over the singer’s self-eulogizing. Snipe Hunter was produced by Rick Rubin (additional production by Tyler Childers and Nick Sanborn), recorded by Ryan Hewitt, Jason Lader and Tyler Harris, mixed by Shawn Everett and mastered by Greg Calbi. All songs written by Tyler Childers. Artists on the album include Childers (vocals, percussion, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, fiddle), James Barker (pedal steel, electric guitar), Craig Burletic (bass, background vocals), CJ Cain (acoustic guitar, electric guitar), Kory Caudill (piano, synthesizer, organ, Wurlitzer, harpsichord, Chamberlin synth, clavinet, jubilee cymbal, background vocals), Rod Elkins (drums, percussion), Matt Rowland (organ, piano, accordion, vocoder, Wurlitzer, synthesizer, mandolin winds, programming, background vocals), Jesse Wells (electric guitar, fiddle, banjo, mandolin, acoustic guitar, background vocals), Nick Sanborn (modular synth, percussion, chimes, vocoder, tape, pump organ), Amelia Meath (background vocals), Alex Sauser-Monnig (background vocals), Olivia Child-Lanning (mouth harp, bow harp) and Kenny Miles (background vocals).