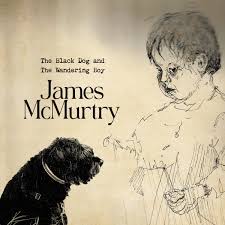

JAMES McMURTRY : THE BLACK DOG AND THE WANDERING BOY

- Laredo (Small Dark Something)

- South Texas Lawman

- The Color Of Night

- Pinocchio In Vegas

- Annie

- The Black Dog And The Wandering Boy

- Back To Coeur D’Alene

- Sons Of The Second Sons

- Sailing Away

- Broken Freedom Song

Label : New West Records

Release Date : June 20, 2025

Length : 44:17

Review (Written In Music) : Het is alweer een tijdje geleden dat de Texaanse singer-songwriter nieuw werk losliet, zo’n vier jaar geleden toonde het met zorgvuldig uitgewerkte verhalen gevulde The Horses and the Hounds het meesterschap van James McMurtry. Dat werkstuk en debuut op New West krijgt nu een opvolger op hetzelfde rootslabel. “The black dog and the wondering boy come around every night, the wandering boy gets any older and the black dog doesn’t bite…” het zijn de woorden die McMurtry’s stiefmoeder hem toevertrouwde naar aanleiding van harnekkige hallucinaties van zijn dementerende vader, de onvolprezen en ondertussen betreurde auteur Larry McMurtry. Het relaas wordt onthuld op donkere harmonicatonen en de gitaarpartijen van McMurtry , worden geflankeerd door bassist Cornbread die de gitaarsolo in de titelsong aanlevert. De vertrouwde bassist Cornbread, drummer Darren Hess en Betty Soo zijn eveneens van de partij samen met de efficiënte coproductie van Don Dixon en hulp van enkele gastmuzikanten zorgen voor efficiënte ondersteuning. McMurtry weet persoonlijke ervaringen om te smeden tot universele verhalen. Bovendien raakt hij politieke pijnpunten aan aan zonder in oeverloos gepreek te vervallen, het door cellotonen ondersteunde Sons Of Second Sons illustreert dat bijzonder treffend. De door jankende gitaren opgejaagde opener Laredo(Small Dark Something), een hallucinante roadsong is afkomstig van John Dee Graham. South Texas Lawman, een lang opgespaard verhaal welde op uit een gedicht van TD Hobart, destijds een vriend des huizes bij de McMurtrys in de jaren zeventig in Virginia. In rustigere, meer folkgetinte, akoestische passages zoals Pinnocchio in Vegas tokkelt James’ broer Curtis op de banjo en zingt even meer. In de knappe troubadoursballade Annie horen we eveneens harmoniezang en banjo, dit keer van Sarah Jarosz. Met Sailing Away over verstoorde satellietsignalen in de buurt van het pentagon die James op weg naar een club in Alexandrië telkens in de verkeerde richting sturen , loopt het stilaan naar het einde, The Black Dog and The Wandering Boy eindigt zoals het begon met een cover. McMurtry luisterde tijdens zijn kindertijd al naar songwerk van Kris Kristofferson, samen met Betty Soo worden we nog verwend met een fijne interpretatie van Broken Freedom Song.

Review (Americana Highways) : James McMurtry has never been one to pull punches, and on The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy, he makes it plain: aging isn’t for the faint of heart. While 2021’s The Horses and the Hounds struck a bittersweet tone about growing older, his latest release dives headlong into the hard truths of time’s toll. “I can’t stand getting old, it don’t fit me,” he growls on the powerful South Texas Lawman. And yet, this album fits him, and these strange days in our country, perfectly. Now in his early 60s, McMurtry continues to prove that few songwriters—inside or outside Americana—can match his lyrical precision. Like John Prine at his sharpest or Guy Clark at his most plainspoken, McMurtry writes with clarity, compassion, and a healthy dose of bite. The Black Dog finds him at the peak of his powers—wiser, wearier, and unflinchingly honest. The record opens with Jon Dee Graham’s “Laredo (Small Dark Something),” a junkie’s lament that McMurtry inhabits like it’s his own. “Living in a motel named ‘MOTEL’ out on Refinery Road” might be one of the most McMurtry-esque lines ever written—and he didn’t even write it. The track sets the tone for what follows: characters chasing ghosts, living with regrets, and holding out for a glimmer of redemption. “South Texas Lawman” sketches a fading sheriff haunted not by crimes but by the quiet unraveling of his life. “His years are empty bottles now / tossed off in the ditch” could be carved on the man’s tombstone. It’s the kind of storytelling McMurtry does better than just about anyone—think Childish Things or Too Long in the Wasteland, now seen through an older man’s eyes. The title track is inspired by one of his father Larry McMurtry’s dementia-induced hallucinations. “The black dog and the wandering boy come around every night,” he sings, conjuring memory, aging, and loss with aching detail. It’s a late-career standout, cut from the same cloth as “Levelland” and “No More Buffalo,” but quieter, darker, more intimate. McMurtry’s gift for turning personal fragments into something universal shines on “Pinocchio in Vegas.” He updates the fable for our modern malaise: “Pinocchio’s over it / he don’t beat up on himself / He’s had to learn to be an asshole / just like everybody else.” It’s funny, sharp, and sad all at once. McMurtry has always been political without preaching, and “Second Sons of Second Sons” is a history lesson as protest song. Its critique of primogeniture and praise for forgotten builders of the American dream recall “Can’t Make It Here” in tone, but with the melodic ease of later-period Springsteen or Steve Earle. It’s an ode to the “overlooked, the younger siblings who helped build a country but rarely make the history books.” It’s melodic, it’s incisive, and like much of McMurtry’s work, it hits harder the more you sit with it. Then there are the quieter cuts. “Annie,” set in the political fog of the early 2000s, reminds us McMurtry is also a criminally underrated vocalist. Sarah Jarosz’s harmony and banjo work here is nothing short of spellbinding. “Back to Coeur d’Alene” might be the best song ever written about the daily hustle of a working musician—its chorus a haunting mantra: “Gotta get known / Gotta get known.” Don Dixon, who produced McMurtry’s Where’d You Hide the Body? back in 1995, returns to helm The Black Dog with a light but sure touch. The production never gets in the way of the songs—it simply gives them room to breathe. The core band (BettySoo, Cornbread, Tim Holt, Daren Hess) is stellar, and guests like Charlie Sexton, Bukka Allen, Bonnie Whitmore, and Jarosz all shine without ever stealing focus. The album closes with Kris Kristofferson’s “Broken Freedom Song,” a wounded soldier’s homecoming set to a slow burn. With BettySoo on harmony vocals, it’s a perfect final note—raw, unflinching, and deeply humane. Like Kristofferson, one of his heroes and biggest influences, McMurtry captures America’s complicated soul in a way few others can. McMurtry has said, “A song can come from anywhere, but the main inspiration is fear. Specifically fear of irrelevance.” The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy is proof that he has nothing to fear. Musicians on the album are James McMurtry on lead vocals, electric guitar, acoustic guitar, 8-string acoustic baritone guitar, and 12-string acoustic guitar; Tim Holt on electric guitar and backing vocals, (electric guitar solo on “The Color of Night”); Cornbread on bass (electric guitar solo on “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy”); and Daren Hess on drums; with BettySoo on backing vocals on “The Color of Night”, “Back to Coeur d’Alene”, “Sailing Away”, “Pinocchio in Vegas”, acoustic guitar and backing vocal on “Broken Freedom Song”, accordion and tambourine on “Back to Coeur d’Alene” ; Jim Brock on drums on “Broken Freedom Song” ; Don Dixon on bass on “Broken Freedom Song”, trombones and slide guitar on “South Texas Lawman”, tremolo guitar on “Sailing Away” and “Broken Freedom Song”, little things here and there; Sarah Jarosz on harmony vocal, banjo on “Annie”; Pat Macdonald on harmonica and backing vocal on “Laredo (Small Dark Something)”, and harmonica on “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy”; Curtis McMurtry on harmony vocal and banjo on “Pinocchio in Vegas” ; Diana Burgess on cello on “South Texas Lawman”, “The Color of Night”, “Pinocchio in Vegas”, “Annie”, and ”Sailing Away”; Sam Pankey on upright bass on “Pinocchio in Vegas”; Charlie Sexton – cum-bus (pronounced jumbush, really and truly, Turkish instrument) on “Sons of the Second Sons” ; Bukka Allen on organ on “The Color of Night” and “Sailing Away” ; Bonnie Whitmore on bass on “Back to Coeur d’Alene” ; and Red Young on organ on “Back to Coeur d’Alene.”

Review (Americana UK) : For 36 years and 14 albums, Texas songwriter James McMurtry has, in a sense, followed in his father’s footsteps, presenting his brand of country noir music as Larry McMurtry embraced literature in novels like “Lonesome Dove.” “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy” is McMurtry’s second release on New West Records, coming four years after he pushed at the framework and notions of roots music with “The Horse and the Hounds.” The new album features appearances by Sarah Jarosz, Charlie Sexton, Bonnie Whitmore, Bukka Allen, and others, as well as his familiar backing band with BettySoo on accordion & backing vocals, Cornbread on bass, Tim Holt on guitar, and Daren Hess on drums. There’s an unhurried sturdiness and maturity to McMurtry’s music. Mostly mid-tempo, these are songs that lope and shuffle along with moored pacing and an organic feel that never places guitar pyrotechnics, of which he is more than capable, over maintaining the story at the centre of the songs. After a first listen, you are inclined to begin scrutinising the songs for the occasional glimpse of what lies beneath the surface impassivity. “You follow the words where they lead. If you can get a character, maybe you can get a story. If you can set it to a verse-chorus structure, maybe you can get a song. A song can come from anywhere,” McMurtry puts forth. To his credit, he is still finding new characters and new ways of telling novelistic stories. As varied as they are, McMurtry’s new story-songs find inspiration in scraps from his family’s past: a rough pencil sketch by Ken Kesey that serves as the album cover, the hallucinations experienced by his father, the legendary writer Larry McMurtry, an old poem by a family friend. A supremely insightful and inventive storyteller, McMurtry teases vivid worlds out of small details, setting them to arrangements that have the elements of Americana but sound too sly and smart for such a general category. Funny and sad, often in the same breath, “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy” adds a new chapter to a long career that has enjoyed a resurgence. ‘Second Sons of Second Sons’ is a lean, direct, sharply-written song with an emotional heft and some of McMurtry’s most evocative insights into the American Dream of sons following their fathers in building the country. His son Curtis McMurtry supplies harmony vocals and banjo on the updating of the fable of the wooden boy with the long nose, er, dick on ‘Pinocchio in Vegas.’ He’s cleaning out the marks at the tables, and like an old Seinfeld skit, “he don’t even need the money; he’s just in it out of spite.” ‘South Texas Lawman’ is a brilliantly restrained song that seems simple but gradually reveals a chasmic depth in the malaise of a career in law enforcement nearing its end. “The hours were long and lonesome / the paperwork’s a bitch / His years are empty bottles now / tossed off in the ditch.” If songs like ‘Back to Coeur d’Alene’ were easy to write, countless Texas troubadours would have written them by now. The life of the travelling musician and the evils of the music business are about as tired subject matter as you can find outside of lost love, but over Red Young’s smooth organ, McMurtry tells the down-and-dirty story: “If my chances are minimal / I’m still giving it all I’ve got / Why do I feel like a criminal / Gotta get known …. Gotta, gotta, gotta.” ‘The Color of Night’ is especially strong, a chugger that builds up a head of steam with a fantastic riff and then coasts deliriously off that momentum for another minute or two. McMurtry’s character is trying to please his Hollywood girlfriend, who is less accustomed to him than being kept in the manner she is accustomed to. “Your candid admission barely thickens the plot / Seems you miss what you’re missing more than you want what you’ve got.” The title track was sourced from his father’s hallucinations as he suffered from dementia before his death. You wonder if McMurtry worries that one day in the future, he’ll be haunted by the black dog and the wandering boy, who will sit at the corner of his bed “Watching for the things that haunt / They ought to both go away when I take my meds / But they don’t.” McMurtry declared, “The album title and that song comes from my stepmother, Faye. After my dad passed, she asked me if he ever talked to me about his hallucinations, but he hadn’t mentioned to me anything about seeing things. She told me his favorite hallucinations were the black dog and the wandering boy. I took them and applied them to a fictional character.” Free of pretences but laden with expectations, this album offers a raw, unfiltered release of longing, restlessness, and ageing. Driven by relatively straightforward yet undeniably moving, guitar-driven arrangements, this is roots rock at its most cathartic. It is evident in ‘Annie,’ with McMurtry’s distressed, defeatist cries of “Not much of nothing on TV” and his solitary admission, “I changed the channel, went up to bed only to wake in the morning and find the World Trade Center gone.” The violence is tempered by lilting harmony vocals and light acoustic guitar from Jarosz. In both its loudest and its quietest moments, “The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy” has few parallels in the power of its songs. Its two covers – Jon Dee Graham’s ‘Laredo (Small Dark Something)’ and Kris Kristoffersson’s ‘Broken Freedom Song’ act as the parenthesis holding the collection together, coming in as a junkie tweaking and going out with a wounded soldier’s homecoming. McMurtry’s gift is his reductive way of presenting a narrative so that his characters, faced with the usual avalanche of anguish, are always laying the breadcrumbs for breakdowns coming to which we all can relate.

Review (Saving Country Music) : James McMurtry is such a master class songwriter and this truth has become so self-evident, you might even hear other songwriters referred to as the “James McMurtry” of their era or region. But James McMurtry is the James McMurtry of James McMurtry’s. He ain’t dead or hung up the guitar just yet. And until he does, and for as long as he continues to release albums, it remains his era. So you best stop down and take a listen, son. A James McMurtry song almost always starts with character and setting, just like the works of his pops, legendary Texas novelist Larry McMurtry. You’ve got to believe that at the age of 63 and nearly four decades into his career, James is probably done with the comparisons. But it’s an apt one nonetheless, whether the younger McMurtry is making fiction, or singing about his own life like in the new song “Sailing Away” that makes references to opening for Jason Isbell, and finds James wondering openly if trying to remain a relevant musician is even worth it anymore. The results of McMurtry’s new album The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy would argue that it definitely is. It’s not just the way he can awaken character and setting in the mind’s eye, and in a much greater efficiency than some long-winded novel. It’s the clever little references he drops in each song, like trying to rip the door handle off your vehicle whenever you’ve locked the keys inside—something we’ve all experienced. Or maybe it’s the reference to a Weird Al Yankovic parody—something that’s probably a little more obscure. But it’s through all of these lyrical mechanisms that McMurtry explores the complexities of human life, and the dilemmas it often creates for itself. Boy the timing couldn’t be better to unveil a song about post 9/11 hysteria and the lessons we didn’t learn from it like McMurtry does with “Annie.” Unafraid to get political, but uninterested in doing so in a simple way that misunderstands the nuance of an issue, McMurtry makes you think, even if you might not agree. In a misunderstood interpretation, some might take the song “Sons of the Second Sons” as a scathing rebuke of the Southern identity as opposed to an exploration into the generational architecture behind endemic poverty and the often fruitless search for leadership out of it. McMurtry’s has a gift for stimulating the brain and broadening perspectives by allowing the audience to see life through someone else’s eyes. Sometimes the lessons of a James McMurtry song to be unraveled are multiple and intertwined. “Pinocchio in Vegas” might initially seem like a humorous hypothetical about the post Disney life of a beloved character. But in truth it’s all about how we often lose precious information about our lives in the passing of our parents. This is the kind of multi-layered songwriting that has put McMurtry at the pinnacle of the craft according to many of his peers. The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy is a distinctly songwriter-based old school alt-country album with some roots inflections, but with a lot of rock influences as well. It was produced by Don Dixon who also produced McMurtry’s third album Where’d You Hide the Body? from 1995. Appearances include Sarah Jarosz, Charlie Sexton, Bonnie Whitmore, and Bukka Allen. McMurtry’s backing band of BettySoo on accordion & backing vocals, Cornbread on bass, Tim Holt on guitar, and Daren Hess on drums are also on the album. While growing up, counterculture icon Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters would pay visits to the McMurtry house. Apparently it was documented in Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Even more crazy, at one point Kesey sketched a picture of a young James McMurtry. It became the cover for the new album. Ken’s widow Faye ended up marrying Larry McMurtry later in life. The title track is inspired by McMurtry’s father’s visions of a black dog and a wandering boy that he would see as he suffered from dementia. Someday, and hopefully well into the future, it will be relevant to broach the subject of who the James McMurtry of the era is. But for now, we still have the actual James McMurtry here with us in the flesh. And as long as he continues to release albums like The Black Dog, it’s his era.

Review (Glide Magazine) : Welcome back, James McMurtry. It’s been four years since 2021’s The Horses and The Hounds. We’ve missed his wit, political insights, and unparalleled storytelling. These new songs on The Black Dog and The Wandering Boy are memories from his family’s past, an old poem by a family friend, confronting old age, outlaw sagas, and both blatant and well-disguised political rants. Well, that’s just some of it. His perspective on songwriting is interesting, as he quips, “A song can come from anywhere, but the main inspiration is fear. Specifically, fear of irrelevance.” That’s not to say McMurtry hibernated for four years. He’s been actively touring, but now he has a fresh batch of songs and an old friend, Don Dixon, producing. Dixon produced McMurtry’s third album, 1995’s Where’d You Hide the Body. Much is made in the promotional materials about the aggregation of guests: Sarah Jarosz, Charlie Sexton, Bonnie Whitmore, Bukka Allen, and others, but their contributions are mostly subtle. McMurtry and his core band of guitarist Tim Holt, bassist Cornbread, drummer Daren Hess, and harmony vocalist BettySoo do most of the heavy lifting. McMurtry is, for whatever reason, a vastly underrated guitarist and vocalist, yet he shines on both accounts in these ten songs, all but two of which he wrote. The opener, “Laredo (Small Dark Something)” is penned by pal, Jon Dee Graham, a junkie’s lament that most would think McMurty wrote, given lines like “living in a motel named ‘MOTEL’ out on Refinery Road.” It’s a scorching rocker that evokes McMurtry’s own Levelland or Too Long in the Wasteland. “South Texas Lawman” paints the kind of precise character sketch that is trademark McMurtry with a chorus of “I can’t stand getting old, it don’t fit me,” only to have the protagonist make the ultimate surrender. “The Color of Night”, with burning guitar from Holt, tells the harrowing tale of a fight that left the protagonist struggling to find his senses, with a chorus that equates the color of night to a 60-watt bulb on a cinder block wall. He takes on the theme of aging again in “Pinocchio in Vegas,” accompanied by Jarosz’s banjo and harmonies with the cinching line. “...He’s had to learn to be an asshole/just like everybody else.” In this sad portrayal, he still manages to make the listener laugh. The title track owes to his stepmother, Faye, who relayed to McMurtry that his dad’s favorite dementia-induced hallucinations involved the black dog and the wandering boy. Another of McMurtry’s hallmarks is his non-preachy, read-into-it-what-you-will protest songs. “Second Sons of Second Sons’ on one level pays tribute to forgotten laborers often overlooked in history books. Yet, this last verse, to these ears, speaks to the cult worship of a certain electorate – “Sons of the second sons, products of genocide/Polishing up our guns, living in double wides/Sons of the peasantry, telling ourselves we’re free/Sons of the pagan serfs/Salt of the fucking earth, in search of Ceasar.” Another hard-hitting political rant is found in “Annie” where McMurtry takes a few shots at the “younger Bush,” suggesting he was in over his head, especially during the Trade Center bombing. There are a couple of lighter songs. The lyrics to “Back to Coeur d’Alene” compare the life of a working musician to upstarts in Hollywood, unable to find a director, each in the quest to gain recognition. In the standout, “Sailing Away’ he and his band are lost near the Pentagon, trying to get to load-in in a club in Alexandria, name-checking headliner Jason Isbell, going on to paint how difficult it is to acclimate once off the road. He bookends the album with another cover, “Broken Freedom Song,” from his idol Kris Kristofferson, whom he began listening to as a youngster. It’s fair to say more than a few lessons sank in.