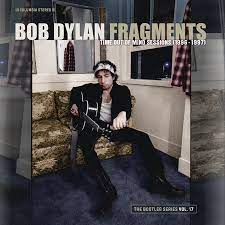

BOB DYLAN : FRAGMENTS - TIME OF OUT MIND SESSIONS (1996-1997) - THE BOOTLEG SERIES VOL. 17

Disc One - Time Out Of Mind 2022 Remix (72:37)

- Love Sick

- Dirt Road Blues

- Standing In The Doorway

- Million Miles

- Tryin' To Get To Heaven

- 'Til I Fell In Love With You

- Not Dark Yet

- Cold Irons Bound

- Make You Feel My Love

- Can't Wait

- Highlands

Disc Two - Outtakes & Alternates (76:13)

- The Water Is Wide

- Dreamin' Of You

- Red River Shore

- Love Sick

- 'Til I Fell In Love With You

- Not Dark Yet

- Can't Wait

- Dirt Road Blues

- Mississippi

- 'Til I Fell In Love With You

- Standing In The Doorway

- Tryin' To Get To Heaven

- Cold Irons Bound

Disc Three - Outtakes & Alternates (76:52)

- Love Sick

- Dirt Road Blues

- Can't Wait

- Red River Shore

- Marchin' To The City

- Make You Feel My Love

- Mississippi

- Standing In The Doorway

- 'Til I Fell In Love With You

- Not Dark Yet

- Tryin' To Get To Heaven

- Highlands

Disc Four - Live 1998-2001 (74:27)

- Love Sick

- Can't Wait

- Standing In The Doorway

- Million Miles

- Tryin' To Get To Heaven

- 'Til I Fell in Love With You

- Not Dark Yet

- Cold Irons Bound

- Make You Feel My Love

- Can't Wait

- Mississippi

- Highlands

Disc Five - Previously Released (73:27)

- Dreamin' Of You

- Red River Shore

- Red River Shore

- Mississippi

- Mississippi

- Mississippi

- Marchin' To The City

- Marchin' To The City

- Can't Wait

- Can't Wait

- Cold Irons Bound

- Tryin' To Get To Heaven

Label : Columbia

Release Date : January 27, 2023

Review (AllMusic) : The key to Fragments - Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996-1997): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17 lies in how the new remix of the 1997 album is described in the box set's promotional material. This new version is supposed to sound "more like how the songs came across when the musicians originally played them in the room," a sideways swipe at the noir patina of Daniel Lanois' production that also reveals how Bob Dylan spent these years chasing a muse he couldn't quite catch. Fragments documents how he kept playing and playing these 11 songs, sometimes tweaking the arrangements, sometimes changing his execution, but usually searching for a performance that captured precisely the right vibe. Given that Time Out of Mind revived Dylan's career, winning the Grammy for Album of the Year as it opened up a third act for the troubadour, it would seem that the singer/songwriter accomplished his goal with the finished record, yet the murkiness of the album nagged at Dylan. This new mix strips all that mud away, leaving an album that sounds like a precursor to Love & Theft and Modern Times: a road-weathered band whiling away the hours at a haunted juke joint. The rest of Fragments consists of alternate takes and live cuts where Dylan keeps hammering away at these songs, occasionally taking a stab at a tune that didn't make the album, such as the previously unreleased ballad "The Water Is Wide," but usually trying to find the right feel. This repetition is accentuated by the recycling of a disc of alternate takes and live versions from this era previously released on The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: it's a lot of samey-sounding material to wade through just to find a slightly different version of "Mississippi." While the remix is instructive, offering insight into Dylan's intentions and making Time Out of Mind seem less like an outlier in his discography, this set is ultimately for the hardcore heads, who don't mind hearing minute variations on familiar themes.

Review (Pitchfork) : ??The official story surrounding Time Out of Mind goes something like this: Bob Dylan, stricken by the death of Jerry Garcia and sensing a hellhound on his own trail, turned to his beloved old blues records to exorcise the quickening dread he felt upon realizing that the bell also tolls for Zimmerman. Dylan, who was only 55 at the time, read his resulting lyrics to producer Daniel Lanois, who was stunned by their unearthly power, and the pair headed into the studio to fashion a record falling somewhere between a seance and a last will and testament. Like all of the stories surrounding the creation of Bob Dylan albums, this one bears traces of myth and marketing. Typically, his Bootleg Series either subverts received knowledge (Trouble No More, Another Self Portrait) or magnifies legends (More Blood, More Tracks, The Cutting Edge). Fragments might be the first release that manages both. The series can feel overwhelming by design or aimed only at the highest-security-clearance Dylanologists, but Fragments presents us with a clear chronology: Disc One gives us the final studio album, remixed and scrubbed fresh so we can avail ourselves once more of its glorious shadows and submerge ourselves in its delicious mood. The remaining four discs—two of unreleased outtakes, one previously available, and a live set—repositions Time Out of Mind as a rebirth rather than a farewell. What becomes abundantly clear over the course of the set’s six hours is that Time Out of Mind is primarily the story of a mood, and one ensemble’s single-minded pursuit of it. The making of this album was protracted, painful, and in all ways alive, and the album’s dour countenance was largely the product of theater and shadow. Dylan, ever the role player, was inhabiting a persona, slipping into a black jacket and working the character for fresh angles. Lanois accentuated the gloom and submerged the album in a damp chill of effects pedals and reverb until Dylan seemed to be speaking to us from the beyond. But—as the new mix on Fragments underlines—his baleful pallor was stagehand’s makeup, the gushing blood just red silk scarves. The story began, appropriately enough, in a picaresque old playhouse Lanois dubbed the Teatro, filled with storybook touches—cob-webbed 16mm projectors, dusty mirror balls. Dylan and Lanois started with looping jams inspired by Charley Patton’s old 78s. Accompanied by bassist Tony Garnier and drummer Tony Mangurian, they built the tracks on top of those primordial beginnings. The mighty, roaring sound that emerged spooked everyone to attention: “The hair on my arms went up,” recalled sound engineer Mark Howard. But Dylan, predictably, wasn’t settling in. He couldn’t work this close to his home and his family, which, by now, included six children and multiple grandchildren. They decamped instead to Criteria Studio in Miami, a space with a hallowed history (Aretha Franklin’s Young, Gifted and Black, the Allman Brothers’ Eat a Peach) and the ambiance of an airport security detention center. Lanois, shrugging, packed up all of his priceless tube microphones and moldering tape loops and relocated without complaint to this concrete box. But it was the beginning of a split between the two that would define and nearly overwhelm the sessions. The two stubborn visionaries seemed destined to remain at loggerheads. Lanois rarely spoke to Dylan before and after takes, and entire days unfolded in icy, uncomfortable silence. Dylan, meanwhile, seemed determined to complicate things as much as possible. He reportedly felt haunted by Buddy Holly, and in tribute, he created his own ghostly version of the Crickets, pulling from his touring lineup, session-player royalty, and beyond. All in all at least 12 musicians found themselves crowded in Criteria, with Bob Dylan as their bandleader (“Two of everything, like Noah’s Ark,” marveled pedal steel guitarist Cindy Cashdollar). Dylan would try songs out in different keys, abruptly switching in the middle and expecting the band to remap their own chord progressions without a moment’s hesitation. The playbacks were a disaster, musicians crashing audibly into one another as they struggled to adapt. Lanois, listening with Howard, knew that he might only have a few shots at catching each song before his tempestuous leader grew bored and moved on, so he ordered musicians to simply not play if they couldn’t navigate the changes. Whatever else was happening in the studio, the musicians achieved a rambling, spacious, loose cohesion. Guitar lines seem to be on the verge of wandering entirely out of sync with the drums only to fall in on beat with a satisfied breath. These are not driving rock numbers, and yet they were three or four drum kits rolling away at any point. The music came on like a big, black thunderhead, rolling forward with guitar echo merging into a clatter of drums. The unreleased outtakes on Fragments reveal some of the extraordinary moments they littered along the path. On Disc 2’s take on the folk standard “The Water Is Wide,” Dylan leans into the performance as if he might reach out and touch the shoulder of his beloved. It’s as devoted as he ever sounded, and behind him, Garnier and Mangurian play so subtly and understated they register as lighting. Disc 5 gives us the original haunting take of “Can’t Wait” that raised Howard’s arm hairs: Over a hard backbeat, Dylan’s block piano chords and impressively tasty riffing from Lanois, Dylan chews the scenery with the unhinged glee of a Shakespearean actor let loose in a Hollywood blockbuster. The song is mesmerizingly dark, but hearing Dylan bite down with panther’s teeth on “I’m getting old,” it’s easy to conclude that he was feeling nothing but the opposite. The extra discs yield the usual Bootleg pleasures: The Disc 2 version of “Cold Irons Bound” features stunning alternate lyrics about “stones in the pathway hurled” and “clouds of blood,” while the live versions of “’Til I Fell in Love With You” and “Standing in the Doorway” inflect the songs with sinewy hints of roadhouse blues, soul, gospel. But the true glory of these recordings is witnessing session legends like Mangurian, Jim Dickinson, and Bucky Baxter—giants whose playing pushed the blood through the veins of American song—sound momentarily lost, reverent, uncertain. The performances on Fragments surely represent some of these players’ most unguarded and searching work. Years later, they still spoke of these sessions with a mixture of anxiety and awe. This lingering unease points to what makes Time Out of Mind special in Dylan’s discography, maybe even singular: More than almost any of his studio albums, it was the product of cult-like group obsession. Everyone from Lanois to Dylan to the phalanx of hired guitarists behaved like people gripped by a shared trance. Sessions stretched to 10 hours while Lanois drove Dylan to try “Not Dark Yet” again in E-flat, then in B-flat, until Dylan finally snapped, “If you haven’t got it now, you ain’t getting it.” Whatever their disagreements or tensions, everyone toiled under the mutual assumption that there were spirits in this material, ones that only they could coax out. Their struggle centered on two songs—“Not Dark Yet” and, ironically, “Mississippi,” a song written for and left off of the final album. There are multiple versions of both songs littered across Fragments, and it is fascinating to hear them expand and contract, changing shapes and keys and tempos. For Dylan, the song had always been the thing: His catalog had always boasted the folk virtues of pliability. You could speed his songs up, slow them down, throw rock drums behind them or do any old thing, and the songs would remain, somehow, themselves: “Desolation Row” remains recognizably “Desolation Row” on take 5 and Take 13. But something different happens to “Not Dark Yet” and “Mississippi” when the players fiddle with them: They become different songs. Listening to the evolution of Time Out of Mind’s most beloved song, “Not Dark Yet,” shows how these lurching, unsteady sessions wound up yielding their particular exhausted glitter. The first alternate take is in a different key, sending Dylan’s voice into a higher register and the song into ill-fitting sunlight; it’s a harmless little ramble. The second take, on Disc 3, is slower, and in the same key as the final version. You can hear Dylan’s voice settle into the tired languor that defines “Not Dark Yet.” But although you get a tantalizing glimpse of its potential, the view is blocked by a marching-band triplet fill on the drums and some Hornsby-esque piano trills. It doesn’t feel gloriously endless, as it does in the final studio version; it simply feels long. It wasn’t until the band stumbled into lockstep, all musicians’ frills burned away, that the song’s dark shadow loomed into view. But the story of Fragments—the story of the album Time Out Of Mind isn’t, but almost was—rests with “Mississippi.” No song undergoes so many fitful revisions. On Disc 2, it’s an uptempo, zydeco-inflected rocker. On Disc 3, the band works it into a gut-wrenching funk that Lanois loved but Dylan rightfully discarded. The definitive version of “Mississippi,” which wasn’t released until 2008 and included on the fifth disc, is suffused with air and light. If “Not Dark Yet” sounded like it was in the beginning stages of evaporation, “Mississippi” felt like fumes itself—far too ethereal and light for Time Out of Mind. Dylan, with his typical foresight, understood this implicitly. This is why he saved “Mississippi” for 2001’s Love & Theft. Critics and fans hailed that one as a rebirth: here, seemingly, was Dylan riding high, Time Out of Mind’s Edgar Allen Poe rags tossed off in favor of a natty bowler hat and a riverboat gambler’s mustache. But Fragments reveals the truth of the matter: The man who croaked about walking through “streets that are dead” already had his glittering blue eyes on the next horizon.

Review (Humo) : 'Wat is een iguanodon?' Dat vroeg het zoontje van een vriend me ooit. Waarop zijn vader hem een lijvige encyclopedie schonk omtrent dinosauriërs. Die de kleine meteen teruggaf met de opmerking: 'Zoveel wil ik niet weten over iguanodons!' Datzelfde gevoel bekruipt mij ook weleens wanneer de Noord-Amerikaanse volkszanger Bob Dylan (81) weer een nieuwe lading officiële 'bootlegs' op de wereld loslaat. Want hoeveel wil ik in godsnaam weten over die wonderlijke man en zijn merkwaardige modern songs? Het gaat bij die bootlegs meestal om een tot de rand gevulde reeks cd's of vinylplaten met daarop archiefmateriaal dat het inmiddels zeer aanzienlijke oeuvre van Heer Bob in een ruimer daglicht stelt, en zo en passant aantoont hoe een meesterwerk geboren wordt. Vaak wordt er een fraai boekwerk(je) bij geleverd, waarin nooit geziene foto's en weldoordachte liner notes prijken die zo voor een fraai en vaak nogal duur hebbeding zorgen.In het begin van dit hopelijk gezegende jaar 2023 werd geboren: 'The Bootleg Series, Vol. 17' voluit 'Fragments - Time Out of Mind Sessions 1996-1997'. En laten we het maar meteen zeggen: voor wie ook maar beetje into Bob is, vormt deze verzameling een onmisbare schakel in het verhaal van hoe de Meester van Duluth uit het dal kwam dat hij in het begin van de nineties voor zichzelf gegraven had. Dit object is, dat had u al door, helemaal opgebouwd rond Dylans universeel bejubelde en commercieel zeer succesvolle 'comebackplaat' genaamd 'Time Out of Mind' uit 1997. Die plaat schitterde, zei men, dankzij de gouden hand en dito oren van succesproducer Daniel Lanois. Nonkel Bob was klaar voor de 21ste eeuw!Kenners, en zelfs wij, vonden 'TOOM' (zo heet de lp in fankringen) een meesterwerk, en ook vandaag klinkt de originele plaat nog hoogst aangenaam. Dylan zingt tegelijk dreigend en rustig, de songs zijn diepzinnig en lang, Lanois weeft er soundscapes rond die harde dingen zacht doen klinken.Iedereen content, zou je denken. Behalve eentje. 'Danny' was geen slechte kerel, liet Bob zich later graag ontvallen, maar van die songs had hij werkelijk niets begrepen. Van moderne blues nog minder.Aandachtig beluisteren van 'Fragments' geeft de meester enigszins gelijk. Songs als 'Cold Irons Bound', 'Love Sick', 'Standing in the Doorway' of het uitklapbare 'Highlands' hebben niet veel tierlantijntjes nodig om onze ziel te treffen. Gepingel en zweverigheid zijn goed voor Lanois, maar niet voor Bob.Het sluitstuk van dit archiefstuk is dan ook de 'naakte' versie van 'TOOM', maar de talrijke bonussen, waaronder vaak verbluffende liveversies van nog niet volgroeide nummers, de zoektocht naar een definitieve vorm voor 'Mississippi' of 'Can't Wait', maken van deze 'Fragments' nu al een waar hoogtepunt in de (never ending?) geheime historie van Bob.

Review (De Morgen) : De duisternis dreigde te vallen over Bob Dylans carrière. Maar toen, in 1997, kwam Time Out of Mind, zijn renaissance. Fragments, het 17de hoofdstuk in The Bootleg Series, toont hoe Dylan uit het dal klom. "Ik dacht echt dat ik weldra Elvis zou zien", zei Bob Dylan na de release van Time Out of Mind. Zijn 30ste album was al opgenomen toen de singer-songwriter uit Minnesota in het ziekenhuis werd opgenomen met een levensbedreigende infectie aan zijn hart en longen, en dan moest de plaat zelf nog komen. "Sometimes my burden is more than I can bear / It's not dark yet, but it's gettin' there", dat moest toch wel over zijn nakende levenseinde gaan? Of, zoals hij het in de zestien minuten durende afsluiter 'Highlands' verwoordt: "I see people in the park, forgetting their troubles and woes / They're drinking and dancing, wearing bright-colored clothes / All the young men with their young women looking so good / Well, I'd trade places with any of them in a minute, if I could." Dylans goede vriend Jerry Garcia, frontman van The Grateful Dead, had voor de opnames het tijdelijke voor het eeuwige ingeruild, en Dylans eigen carrière leek al met één been in het graf te staan. Dylans dorre jaren 80 waren dan wel afgesloten met het mooie Oh Mercy, maar het daaropvolgende Under the Red Sky gaf aan dat berichten over een comeback voorbarig waren. De songs waren op, zo leek het wel: zijn volgende twee albums, Good as I Been To You en World Gone Wrong, bevatten alleen traditionele standards. Dik 25 jaar na de release van Time Out of Mind - een kwarteeuw waarin de inmiddels 81-jarige bard de langste creatieve bloeiperiode uit zijn carrière beleeft - is het bijna moeilijk om je in te beelden dat Dylan onzeker was over het dik dozijn songs waarmee hij naar producer Daniel Lanois stapte. De U2-knoppendraaier (die ook achter de mengtafel zat tijdens Oh Mercy) drukte Dylan op het hart: "Ik denk dat we een album hebben." En maar goed ook: Dylan zelf vond voordien dat hij klaar was met songs opnemen, gaf hij jaren later toe in Rolling Stone, maar zijn platenmaatschappij had hem een contract aangeboden dat hij "niet kon weigeren". De drie Grammy Awards voor het album zou hij evenmin afslaan. Maar misschien had Time Out of Mind nóg beter kunnen zijn. Tussen de zestig tracks van Fragments, het zeventiende hoofdstuk in Dylans Bootleg Series, zit onder meer 'The Water Is Wide', een warm bad van melancholie, dat niet op Time Out of Mind had misstaan in plaats van 'Make You Feel My Love'. Volgens zangeres Adele maakt haar hitgevoelige cover uit 2008 Dylan nog "een miljoen pond per jaar" rijker, en ook Billy Joel (zijn cover kwam nog uit vóór de Dylan-versie) en Jasper Steverlinck grepen naar het brede appeal van de song, maar op Time Out of Mind wringt hij toch een beetje. Mooi liedje, daar niet van, maar de romantische schmalz misstaat tussen de droefenis, de eenzaamheid en zelfs de verbittering die de plaat inkleuren. De nieuwe, heldere mix van de 11 albumtracks waarmee Fragments opent, benadrukt eens te meer hoe scherp Dylan klinkt op een song als opener 'Love Sick'. Het verschil met de originele plaat is niet hemelsbreed, maar het is al lang geen geheim meer dat Dylan niet tevreden was over Lanois' productie - alles wat nadien volgde zou hij zelf produceren - en op Fragments wordt Time Out of Mind gestript van de sfeervolle, wazige sound die Lanois uit de knoppen had gedraaid. De outtakes en alternatieve opnames laten zelfs nog spaarzamere arrangementen horen. Tussen Lanois en Dylan kwam het overigens geregeld tot aanvaringen: de zanger moest niet al te veel weten van het amalgaam aan muzikanten dat de producer voor de sessies had verzameld, en hun visie over hoe de bluesy songs juist moesten klinken, lag soms mijlenver uit elkaar. "Lanois is een uitstekende producer", gaf Dylan enkele jaren later wel toe in Rolling Stone, en "hij kan heel gepassioneerd zijn over wat hij denkt dat klopt". Dat uitte zich weleens in kapotgeslagen gitaren, vertelde de latere Nobelprijswinnaar erbij. "Dat kon me nooit schelen, tenzij het er een van mij was. De boel kwam een keer onder hoogspanning op de parking. Hij probeerde me ervan te overtuigen dat een song 'sexy, sexy en méér sexy' moest zijn. Maar ik weet ook wel wat van sexy", vertelde Dylan, die het na het succes van Time Out of Mind tot in een Victoria's Secret-commercial schopte. "Maar hij had zijn eigen manier om naar de zaken te kijken, en uiteindelijk moest ik dat afwijzen want ik hechtte te veel belang aan de expressieve betekenis achter de teksten om ze te begraven in een stomende hutsepot van drumtheorie." De 14 livetracks op Fragments - waarvan er 2 eerder verschenen op Tell Tale Signs - beklemtonen de meesterlijke simpliciteit van Dylans songs. De opnamekwaliteit is niet om over naar huis te schrijven en de opname van 'Not Dark Yet' uit 2000 klinkt misschien een tikkeltje te melig, maar het snedige livearrangement van ''Til I Fell In Love With You' toont dat Dylan na de opnames van Time Out of Mind de onzekerheid van zich heeft afgeworpen en wíst dat hij nog steeds een songschrijver par excellence was. Fragments laat horen hoe Dylan na 35 jaar in zijn carrière werd herboren. Dit keer niet als vrome christen, zoals twintig jaar eerder, maar als levende legende.