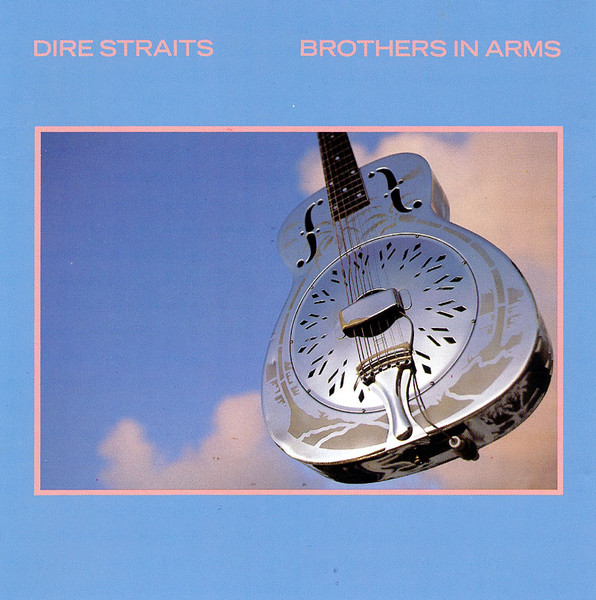

DIRE STRAITS : BROTHERS IN ARMS

- So Far Away

- Money For Nothing (with Sting)

- Walk Of Life

- Your Latest Trick

- Why Worry

- Ride Across The River

- The Man's Too Strong

- One World

- Brothers In Arms

Label : Vertigo

Release Date : May 17, 1985

Length : 55:14

Review (AllMusic) : Brothers in Arms brought the atmospheric, jazz-rock inclinations of Love Over Gold into a pop setting, resulting in a surprise international best-seller. Of course, the success of Brothers in Arms was helped considerably by the clever computer-animated video for "Money for Nothing," a sardonic attack on MTV. But what kept the record selling was Mark Knopfler's increased sense of pop songcraft - "Money for Nothing" had an indelible guitar riff, "Walk of Life" is a catchy up-tempo boogie variation on "Sultans of Swing," and the melodies of the bluesy "So Far Away" and the down-tempo, Everly Brothers-style "Why Worry" were wistful and lovely. Dire Straits had never been so concise or pop-oriented, and it wore well on them. Though they couldn't maintain that consistency through the rest of the album - only the jazzy "Your Latest Trick" and the flinty "Ride Across the River" make an impact - Brothers in Arms remains one of their most focused and accomplished albums, and in its succinct pop sense, it's distinctive within their catalog.

Review (Mojo Magazine) : Of all the artists to herald the digital age with its shiny new compact disc format, Dire Straits were surely the least likely. Workhorses rather than high-gloss show ponies, they emerged from London’s mid-’70s pub rock circuit featuring two former members of Brewer’s Droop, playing country-tinged blues boogie written by a self-effacing ex-newspaper reporter and schoolteacher from Newcastle. Mark Knopfler had tried many other jobs before rock’n’roll, and beyond inculcating respect for hard graft and emphasising where his gifts truly lay, none prepared him for leading the world’s biggest band. Which is pretty much what Dire Straits became on the back of their fifth album. Brothers In Arms was UK Number 1 for 14 weeks and spent nine weeks on top of the US chart, scooping up worldwide sales of over 20 million, driven by a year-long world tour numbering 248 shows and a string of hit singles, none bigger than Money For Nothing, a Billboard Number 1 turbo-charged by its state of the art computer-animated video, to all intents and purposes an advertisement for MTV, which duly repaid the debt in endless rotation. Thanks to these numbers and legacy, Brothers In Arms ceased to be a mere album and became a pop cultural avatar – imagine a silver 1937 National Resonator guitar slapping you in the face, forever. It’s ironic that a record which became synonymous with ‘more’ began as an attempt at less. Knopfler was craving a return to roots, after 1980’s Jimmy Iovine-produced Making Movies had powerfully upgraded the 1978 debut’s backroom choogle, and then 1982’s still-extraordinary Love Over Gold, an epic suite of abstract expansions plotting the geometry of thin air in ways that would be subsequently pursued by Talk Talk and Radiohead. Yet in the interim he’d also made some movie soundtracks – most notably Local Hero, where his theme was as much the star of the film as either Burt Lancaster or the Scottish Highlands – and bought a Synclavier digital synthesizer, then hired Roxy Music’s Guy Fletcher to play it. Ergo, essentially, Brothers In Arms: songs like So Far Away and Why Worry are intense miniature dialogues transposed to widescreen and filigreed with the latest tech. The former feels like a dustbowl motorik refugee from Avalon, while the latter’s lonesome melodies and hanging chords were soon enough acknowledged worthy of an Everly Brothers cover version. The album’s most minimal song, tellingly Why Worry was also its longest. The Cajun trifle Walk Of Life became a radio perennial but it was never more than a throwaway ditty, and indeed co-producer Neil Dorfsman wanted to do just that; the Knopf said no, he felt its charm, and got his way. Knopfler’s gift was always to see the significance in minor inflections, be they emotional or musical. The Man’s Too Strong, meanwhile, is as low-key as a Celtic-tinged character study of a suspected Nazi war criminal possibly could be. Amid these embroidered cameos land the epic set-pieces: Your Latest Trick whiffs of mid-’70s Bob Dylanjamming with Steely Dan, complete with the Brecker Brothers giving it the full lounge act. Knopfler had played with them on Gaucho’s Time Out Of Mind, a reportedly stressful experience for him, but this time they were playing to his tune. Ride Across The River is Bruce Springsteen gone white reggae for a woolly dogs of war tableau. Better by far is the title track’s haunted battlefield evocation, barely there but speaking louder for it, spiralling upwards like Pink Floyd with warm blood in the veins. In Paul Sexton’s sleevenotes for the deluxe edition, Knopfler reveals the title came from a comment his father made about the Falklands War and the irony of the Soviet Union backing a fascist government in Argentina. Of course, much of Brothers In Arms’ lower-case intrigue is eclipsed by Money For Nothing, and how could it not? The greatest riff Billy Gibbons never wrote; the cameo from Sting, dragged in off the beach and asked to sing “I want my MTV” to the tune of one of his own songs; and a notoriously jarring lyric. Knopfler was not the first to discover that pop songs aren’t the safest vehicles for hiding an obnoxious narrator, but as a deep fan of Randy Newman he perhaps ought not to have been too surprised when people were offended by his voicing a pair of hardware store workers watching a “little faggot” playing guitar on the televisions they were shifting. Come the BIA tour he was already self-censoring, and whatever subversive commentary the song had to offer on the process of fame – a rock star who hated videos singing a song satirising people who resent rock stars, watching a rock star’s video – was rendered moot. This fortieth anniversary version is unlikely to shift the critical dial on a record about which most people have long since made a decision. There are no alternate studio takes suggesting paths never taken, which is a shame, as the sleevenotes trace the pre-production process from Knopfler’s west London mews to Ray Manzanera’s studio in Surrey and thence to George Martin’s fabled AIR outpost in the Caribbean. Almost all drummer Terry Williams’ contributions in Montserrat were replaced by jazz session ace Omar Hakim, and if still exist somewhere they’re not here. At least Terry was back on the stool for the BIA tour, which provides the only real inducement for diehard fans to buy: the deluxe edition has the entire unreleased San Antonio concert from August 16, 1985, a faithful representation of how far a groovy little rock’n’roll band had gone in just under 10 years, the two remaining original members surrounded by two extra keyboardists, saxophone and percussion, their songs appended with yawning intros and multiple crescendos that threaten to secede from the thing they’re ostensibly bringing to a close, not a single note out of place. Amid it all, Knopfler’s virtuosity remains somehow both transcendent and earthy, his perennial saving grace. By the end of that 1985-86 tour. Mark Knopfler was as tired of Dire Straits as anyone. Five years elapsed before the follow-up to Brothers In Arms, 1991’s scruffier, even longer On Every Street, after which he called time on the whole dog and pony show, fed up with being famous for just playing his guitar on that damn MTV. “Success I adore,” he told Sylvie Simmons in a 1996 interview. “As far as I can see, fame is just a waste-product of success.”