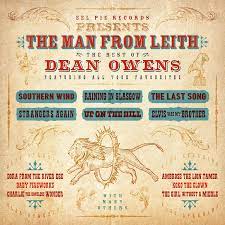

DEAN OWENS : THE MAN FROM LEITH - THE BEST OF DEAN OWENS

- Man From Leith

- My Town

- Up On The Hill

- Strangers Again (with Karine Polwart)

- New Mexico

- Virginia Street

- Elvis Was My Brother

- Baby Fireworks

- Evergreen

- Dora

- Southern Wine

- The Night Johnny Cash Played San Quentin

- Whiskey Hearts

- Closer To Home

- Raining In Glasgow

- The Last Song

- Lost Time

Label : Eel Pie Records

Length : 71:17

Release Date : 2020

Review (Folkradio) : The first Scottish musician to officially showcase at Nashville’s Americana Fest in 2017 and the title track from Southern Wind winning the American Music Association UK Song of the Year Award for 2019, Edinburgh-born Owens has had a long and celebrated near 20-year career. Starting initially as the frontman for Scottish alt-country outfit The Felsons and, most recently, as part of Buffalo Blood alongside Neilson Hubbard, Audrey Spillman and Joshua Britt. Cherry-picking from his seven official solo albums, this collection highlights his strengths as both storyteller and singer, imbuing his love for Americana with a Scottish sensibility with songs that are both personal and universal, factual and fantasy. Three numbers, relate directly to his family, the first, from Whisky Hearts, being the six-minute plus the opening title track, a tribute to his father who worked both the Leith dockyards and on the roads across Scotland, beginning with church organ and etched out with a hymnal melody and back porch steel guitar. The other two are both taken from 2015’s Into The Sea, Dora being a Celtic tingled steady drumbeat Americana jangle, complete with whistling, that tells the true story of his grandmother, Dora Salvona Owens, the daughter of travelling circus family, her father a high wire performer who, still a young man, was killed in an accident at Leith docks in 1938. As he sings “you never know what’s up there, way up in the family tree”, the song also references his great-great Italian grandfather Ambrose Salvona (and his dancing bear), the circus founder and lion tamer, noting “He’s buried in the Highlands/but we’re not sure where.” Following the album’s release, his grave was tracked down to Inverness along with the fact he was a buried, to a Salvation Army band salute. The other, featuring Kim Richey on harmonies, is Evergreen, a bittersweet piano-backed ballad written in response to his sister and a friend both suffering from cancer. The same album also includes two songs inspired by where he grew up. Up On The Hill is about the place in Edinburgh where he walks his dog and finds time to think and reflect on those he’s lost and the paths he must follow. While Virginia Street, inspired by a conversation with a friend in a Glasgow pub, takes what I would assume to be the Leith thoroughfare as the backdrop for a warm reflection on an old love affair. The final number from the album is the simple strummed Closer to Home, inspired by a documentary about World War I, the chorus of “the closer to home, the harder it is to bear the distance” taken from a letter written to his wife by a soldier returning after the end of hostilities. The earliest track, the fiddle accompanied lost love Hispanic–toned slow jogging New Mexico (incidentally, where he recorded the Buffalo Blood album) dates from his 2001 solo debut The Droma Tapes, while the 2004 follow-up, My Town, provides two. First up is the title cut love letter to home with its warm brass band opening and slow waltz rhythm, the other being the uptempo countrified brushed drums waltzing Strangers Again, a lovely broken relationship duet with Karine Polwart, who, as this shows, really should record Americana more often. Moving on to what is generally regarded as his breakthrough album, 2008’s Whisky Hearts, the sway-along mandolin-strummed title track about the effects of the dockland closures with its snapshots of drowning broken hearts and the ache of loss is paired with the classic homesick Raining In Glasgow, a slow march, piano-backed number written in Australia where he imagines himself at Barrowlands “watching Elvis Costello and the Attractions playing Pump It Up”. He released two albums in 2012, each represented by a song apiece. From his fourth album, the somewhat overlooked New York Hummingbird, recorded in New York and New Jersey, comes one of the stronger moments with the piano and percussive sparkly mid-tempo chug of Baby Fireworks. The year’s second release was his Johnny Cash tribute, Cash Back, marked here by its sole self-penned number, The Night Johnny Cash Played San Quentin, a strummed, dobro-streaked dead man walking prison song that perfectly channels the country legend’s spirit. The remaining three cuts are lifted from 2018’s Southern Wind, a return to strong form with two numbers here co-penned with guitarist Will Kimbrough, the big production title track being a slow march, blues and gospel-informed number about the call of home also featuring swirling organ from Dean Mitchell, the Worry Dolls on harmonies and the big voice backing vocals of Kira Small. The other, The Last Song, though, paradoxically, the first written for the album and its opening track, a bouncy end of the night countrified pub rock number drawing on a mutual love of Ronnie Lane and The Waterboys. The final number again draws on real-life and stories told, this being Elvis Was My Brother, a jaunty, guitar twanging song inspired by a letter from a friend who, raised by his mother, frequently uprooted and with little contact with his father, found a friend and brother listening to Elvis on his mother’s cassettes. Frustratingly, Owens probably enjoys greater critical acclaim respect than he does sales, but, as well as offering a career snapshot for the faithful; this serves as a handy enticement to newcomers to dig further into the catalogue and discover what they’ve been missing. Later this year, pandemics willing, he’s due to record a new album in Tucson with desert noir icons Calexico, I for one can’t wait to hear it.

Review (Maxium Volume Music) : Ask me about Leith or Edinburgh and generally the first two things that come to mind are the Rebus books. I read all these things, and the city became intertwined in my mind with them. Second, though, is a family holiday that we spent there in the early 90s. My parents loved Scotland, we went there quite a few times, but on one occasion we did a bit of a tour, starting in the South West, moving to the Highlands and its rugged beauty, before ending in the capital. A beautiful city, me and my younger brother bought touristy things to show our grandparents and put in the scrapbook we always made, our late mother was convinced she’d seen Stephen Hendry, the snooker player, and my dad got in a row with a steward at the castle, I can’t remember what about, but I do remember dad saying something that I’d never heard him say before: “never trust a stupid man in a uniform, And. Never.” He’s said it about million times since, bless him, and it is probably where I get my disrespect for such things from. The reason for this reminiscing? Well Dean Owens, actually. It’s like Irvine Welsh says in his brilliant sleeve notes for “The Man From Leith”. “Dean Owens’ music feels like a tribute to the songs inside us, the tales of our lives, reaching in us to find our common humanity”. And listening to the 17 tracks that make up this astonishing career (so far) retrospective, then my mind wandered back to those days, the four of us, and I make no apologies for it, either. Owens, I am sure, wouldn’t want me too, because he deals with such minutiae too, not least on the opening, title track, a beautiful tribute to his own father, and when it got to the line about “the blood of the father flows through the veins” all I could recall was all the rows I’ve had with stewards at football, at gigs, everywhere, before smiling, wryly. The best singer songwriters (and on his notes for this Owens calls himself that rather than a musician) the Springsteen’s the Dylan’s, the Jason Isbell’s, the Stephen Fearing’s of the world, make us think about our own lives in their words. And time and time again that’s what these wonderful things do. “My Town”, somehow made more evocative with the violin work, or “Up The Hill” which sounds appropriately widescreen and hewn from the landscape, are exactly why Owens became the first Scot to play Nashville’s Americanafest in 2017. Accolades come his way – not just Welsh, but Bob Harris is amongst his fans – and he’s won song of the year at the AMA awards in 2019, but somehow you imagine these aren’t as important as the quality of the work. He records mostly in America – the superb Will Kimbrough co-writes a couple of these – and “New Mexico” is as dry as the dusty desert, while “Virginia Street” sounds oddly Scottish, Del Amitri, Roddy Frame, pick who you like. One of the highlights, perhaps is “Elvis Was My Brother”, a stunning thing about losing yourself and finding yourself in music. Another of the best is “Evergreen” from the title track of his 2015 record, written in the wake of the tragic death of his sister from cancer, and if “family” is a concept never too far away, then “Dora” the story of his circus performer grandmother underlines its importance. Arguably the best of them all, though, is “Southern Wind”, one of the ones written with Kimbrough, the way that builds and almost – for want of a better word – explodes is quite magnificent, and the harmony vocals are important here, too. Often – again like the best – he finds an angle that no one else would. “The Night Johnny Cash Played San Quentin” is one example. From his album in tribute to Cash, this was the only self-penned one. From the perspective of an inmate watching the gig, and just for a little while being free. “Whisky Hearts”, with its harmonica intro, is easily seen as a kind of Celtic Bob Dylan, while the darkness, the melancholy, the longing on “Raining In Glasgow” is still somehow beautiful. It is juxtaposed by the overt country of “The Last Song” and the very last one on this, “Lost Time”, just Dean and his guitar, it is fragile and glorious. In what he writes on the sleeve Owens says he feels like he shouldn’t be doing a “Best Of” as he’s “just getting started” – that’s, with respect, to miss the point, given that if this 70 odd minutes reaches someone, anyone new, then it’s worth it, given that he deserves to be seen as up there in the very top of the tree. Elsewhere he says that he uses musicians as “the talented people to make my songs sound like I hear them in my head”, and certainly the music augments them, but the real genius lies in the vocals and the words. And they are all from a Man From Leith.