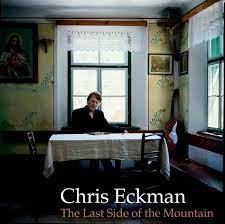

CHRIS ECKMAN : THE LAST SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN

- Bells Of A New Day

- Down, Down

- Eyes

- Ransom

- Who Will Light Your Path? (With Anita Lipnicka)

- Stranger

- Scorpions

- Hours

- The Same

- With What Mouth

- The Last Side Of The Mountain

- Fragment

Label : Glitterhouse Records

Release Date : November 3, 2008

Length : 42:01

Review (Elsewhere) : Eckman has been one of the cornerstones of the long-running and very credible alt.country outfit the Walkabouts, has released solo albums, and been a member of the ever-evolving Willard Grant Conspiracy. All of which should recommend him if you follow this particular path of string-augmented, soul-baring songwriting. But the material for the bulk of this album comes from an unusual source: here Eckman sets to music some of the stark poems of the late Slovenian Dane Zacj who he places in the pantheon alongside Townes Van Zandt. There is an elemental quality to these images and lyrics, and the indifference of the world, the price you'll pay for life, matters of belief and other weighty ideas. But Eckman sets them to memorable (beautifully produced, and intimate or uplifting) melodies. Guitars gently soar, synths add scale and texture, the orchestration is supportive and elevating. Certainly some may hear this as earnest as Bono at his most breathy and self-important, but that would be a superficial reading of what is here: these are powerful poems with real depth and resonance. Originally from Seattle, Eckman has been living in Slovenia for many years and here brings that quality to the music too in the company of local players. One to definitely check out and immerse yourself in. Especially if the name Leonard Cohen means anything to you.

Review (Penny Black Music) : It was inevitable that having been given as a gift a translation of ‘Barren Harvest’, one of Dane Zacj’s sets of poems, that Chris Eckman would find much to identify with in the late Slovenian poet's verses. The Seattle-born but now Llubljana-based Walkabouts front man and solo singer-songwriter comes from a similar place of the soul to Zajc, sharing with him an earthy fascination with nature and the elements, corresponding thoughts on the uneasiness of communication between the sexes and the same dark romanticism. For his latest solo album ‘The Last Side of the Mountain’, Eckman has taken nine of Zacj’s poems and set them to music. Musically ‘The Last Side of the Mountain’ finds Eckman on firm but familiar territory, merging together the celestial choirs and orchestras, epic soundscapes and gorgeous melodies that have dominated many of his recent albums with both the Walkabouts and in his solo career. ‘Who Will Light Your Path ?’ is especially beautiful, a duet between Eckman and the sultry-voiced Anita Lipnicka that muses on the uncertainty of the future and love(“Who will wait for you at the crossroads ?At midnight towards what light will you turn ?”), and which sets together echoing strings with a pulsating synthesiser and an acoustic guitar. ‘Stranger’ is, however, rougher in tone, a rattling, metallic-in-sound blues number with grinding guitars and a wailing harmonica which is about how the dead live on in the mind and the memory (“Are you warm now, stranger ?/Was your cold spirit finally warmed by the fire in your flesh ?”). 'The Same’, another duet, this time with former Dream Syndicate front man Steve Wynn, (whose album ‘Crossing the Bridge’ Eckman produced last year), which is about the thought that everyone has a double somewhere in the world, is meanwhile with its raucous vocals and discordant music genuinely eerie and chilling (“In another world, the same/The other in the same world/The same in the same world”). The title track is an instrumental with tolling bells and slowly surging strings that builds up to the climax of the album in which, as all the music suddently drops away, Zacj himself makes a brief appearance at the end of the record reading part of a poem in Slovenian. By its very nature, and in being essentially the musical adaptation of the work of a dead poet little known outside of his own country, ‘The Last Side of the Mountain’ seems destined to become one of Eckman’s lesser known works. Genuinely enthralling and exciting, it,however, more than bridges and fills the gap for this prolific songwriter before either the next album of his own material or long awaited new Walkabouts’ record, the latter of which has been promised for later in the year, comes out.

Notes (Chris Eckman) : A few years ago I was having coffee in the center of Ljubljana with my friend Tomo Brejc. While we were waiting to order, he pulled a book from his bag and handed it to me as a gift. The book was "Barren Harvest", an English language poetry collection by the Slovenian poet Dane Zajc. Tomo is a photographer of great re-known, and had been asked to photograph Zajc for the cover of the book. He had been given a few copies and thought that Zajc's verse would be something that I might identify with. How right he was. I took "Barren Harvest" home that afternoon and read through it in one sitting. The next day I did the same, and the day after that, the same thing again. Rarely had I been so struck by a book of poems or a work of art in general. After several more readings Zajc's poems had joined company with Townes Van Zandt's "Our Mother the Mountain," Terrance Mallick's "Days of Heaven" and Richard Ford's "Rock Springs" in my own personal Pantheon of artistic inspirations. The poems are stark and direct. They are pointed but never hysterical. They read gracefully, but they are not digested quickly. They are poems aware of the vagaries of solitude and personal struggle but they ruthlessly avoid vanity and voyeurism. They are never reductive, never simply sad, or simply optimistic. They are poems about the joy and failure of language itself. They are often written as impassioned, open-ended dialogues: the poet in dialogue with his fears; with the absent creator; with his lovers, with the reader and even with those who have passed beyond. The poems are rarely pleasant, but they are consistently generous and honest. They always manage to strike a nerve. They always elicit contemplation and complexity of feeling. I have grown to deeply identify with Zajc's sharply chosen words and resonant images. The rich, imposing landscapes (mountains, deserts, forests), the animals of prey with their unrepentant truths (wolves, scorpions, snakes), and the vivid reports from wanderings into lost, hallowed places. Throughout his work, Zajc stoically searches, as the poem says, for "a new language of the earth." A language fashioned from cosmic skepticism and from hands turned dirty from the hard work of living. A language turned up from the mother soil itself, where landscapes actual and metaphorical collide and enchant. This may seem sacrilegious to those in Slovenia who hold him as a national icon, but when I read these poems I am always transported to the great wide-open of my ancestral home in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Poems like 'Stranger" or "Scorpions" or "Eyes" are dramas that could easily unfold in the sublime, and even harsh environments found in the glacial mountains and high deserts outside of Seattle. And while I would never dare to say that there is not something specifically Slovenian about Zajc's world view, I will say that his work speaks very directly to my own experiences and journeys. I believe him to be quite portable, quite universal. Very early in my encounter with his poems I began to dream about turning them into songs. It had been done before. The Slovenian insurgent cabaret act Compe had fashioned art songs out of several of his poems and Zajc himself performed frequently with Compe's accordionist Janez Škof, in a musical duo, where Zajc half -intoned, half -sang his creations. But the idea that started to appear to me involved doing things a bit differently. Generally, there is a strong strain of lyricism in Slovenian poetry, and it is probably not a linguistic accident that in the Slovenian language, the word for song ("pesem") is, the same as the word for poem. Following this tradition, many of Zajc' poems are profoundly lyrical, at times even suggesting the traditional folk song structure of verses and refrains. This was more the direction I wanted to explore. I wanted to see if I could move the powerful voice of these poems into the realm of traditional song without doing unnecessary violence to either their cadence or their meaning. Of course, when one is working in translation, the question of "meaning" is a thorny issue. Them are inevitably many things obscured, many things misplaced. It is an imperfect pursuit. I took this element of the project very seriously and combed all the existent English translations of Zajc's work, and had new translators also take a turn at the poems. On several occasions, I had to slightly deviate from the chosen translations to accommodate the melody or rhythm of the songs I was writing. I also created refrains by repeating certain stanzas from the poems. These things aside, I tried to keep my textual artistic license to a minimum. In the end though, as with any act of adaptation and translation, these songs are at best versions of his words, cut from the original cloth but stitched together by an immigrant tailor, using a borrowed needle, and a different colored thread. Dane Zajc sadly died in October of 2005. I never had a chance to meet him, or to play him the songs that I wrote, but we did have singular, memorable phone call. The poet AI. Debeljak and his wife Erica Johnson Debeljak (the translator of the above mentioned book "Barren Harvest") had told Z.ajc of my plan to make English-language songs out of his poems. Apparently Zajc said he was interested in discussing the project, and I was invited to give him a call. I was extremely nervous and kept delaying making contact, because frankly I was star struck. I admired the poems so much that I was afraid that I would not be able to talk clearly to the man who had written them. This actually turn. out to be the case. Once I had him on the phone I stammered, and stumbled and delivered a string of stilted, confused sentences that did very little to make a convincing case for my idea. The poet listened graciously and after I paused to take a much-needed breath, advised me to: "Just do it." If out about Zajc's death after I returned to Ljubljana from a European tour. I had planned to start writing the songs that Autumn, but the tragic new, wore hard on me and I began to think that it was best not proceed with the project. I felt that maybe it was too much of a responsibility without him around as a potential sounding board. I certainly did not want any of my own inadequacies as a songwriter or a musician to veil the beauty and fluency of his poems. My wife and a couple of friends softly pushed me to reconsider. But in the end, it was those three words that Zajc had said to me on the phone that led me forward. "Just do it." Well, here it is. It is done. And if you find any shards of truth or magic inside these songs, they belong to the poet. The one who spoke with a tongue of soil.