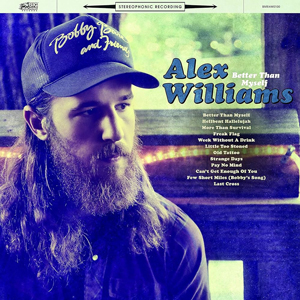

ALEX WILLIAMS : BETTER THAN MYSELF

- Better Than Myself

- Hellbent Hallelujah

- More Than Survival

- Freak Flag

- Week Without A Drink

- Little Too Stoned

- Old Tattoo

- Strange Days

- Pay No Mind

- Can't Get Enough Of You

- Few Short Miles (Bobby's Song)

- Last Cross

Label : Big Machine Records

Release Date : 2017

Length : 48:55

Review (Saving Country Music) : When will country music be saved? When traditional country artists and quality songwriters are given equal billing right beside their pop and modern country counterparts on the radio, at award shows, on tour, or anywhere where country music is celebrated and recognized. It’s a seat at the table; an opportunity to espouse and ply the traditional roots of the genre without the burdens of obscurity relegating the music to inferior channels. That’s why whenever a traditional country artist, especially a young one, emerges from a major Nashville label, it is worth paying extra attention to. If 90% of mainstream music is garbage, it stands to reason that 10% isn’t. It’s that 10% where not only some good listening can be found for traditional country fans and folks who lean more towards the Americana side, it’s also what must be celebrated in hopes that the percentage of good stuff rises. The Big Machine Music Group is the home of Taylor Swift, Florida Georgia Line, Thomas Rhett, and a host of other villains to in the traditional and Outlaw music communities. But it’s not as if Scott Borchetta’s label has never championed quality country, or projects where the commercial possibilities are limited. It was Big Machine that released Saving Country Music’s 2013 Album of the Year, The Mavericks’ In Time. The label recently released a record from Aaron Lewis, and regardless of what you think about the Staind frontman personally, it’s hard to not call that record country. You can even point to Midland as a recent Big Machine experiment into the more traditional side of the genre. But Alex Williams is not like any of those. Aaron Lewis and The Mavericks already had established names when Big Machine came calling, and even though Midland is more traditional than what the mainstream is used to, they have an image that people are buying into, and an actual radio strategy that has been pretty effective so far. With Alex Williams though, you have none of that. He’s a virtual unknown. Yet here he is releasing a by God traditional country record through arguably the most powerful major label in “country” music. There is no need to mince words here or parse expectations. Alex Williams debut record Better Than Myself is traditional country music. And if it needs any qualifiers, it would be that it leans more toward the Outlaw style. There’s no compromise, no songs getting intro’d with a drum machine beat. It is true country music in every sense. Williams (no relation, by the way), who is originally from Indiana, wrote or co-wrote every song on the album. And just taking a look at him, this is not a guy trying to squeeze by on his Hollywood looks. With his long beard and hair, he could fit in right beside Cody Jinks and Whitey Morgan on an Outlaw festival lineup. alex-williams-better-than-myselfBut as has been said on Saving Country Music many times, just because something is real country doesn’t mean it’s real good. The songs still have to say something. There still has to be an element of originality. Making true country can be difficult because you must adhere to established rules, yet find a way to innovate and put your signature stamp on the music within those rigid parameters. Frankly, the most intriguing thing about Alex Williams and Better Than Myself is that it’s originating from Big Machine. When you start listening, despite the infectiousness and joy you find in the moaning steel guitar and twangy vocals, the lyrics rely often on fairly cliché drinking and smoking themes that have been worn out for many years. It’s not that drinking songs are a bad thing, but how do you write and sing one anew? Alex Williams struggles a bit with that in some of the tracks pushed out to the forefront to represent his style, songs like “Hellbent Hallelujah,” “Week Without A Drink,” and “Little Too Stoned.” “More Than Survival” is basically a Bro-Country song set to a more Outlaw country style. Alex Williams directly cites Cody Jinks as one of his influences, but there’s no “David” or “I’m Not The Devil” on this record. It mostly represents the party hearty, renegade side of country, without much of the pain, struggle, or redemption that has always been at the heart of “Outlaw” country music, and overlooked by those who only take shallow observances of what an Outlaw is based on image and style. Is Alex Williams just Big Machine seeing the success of Cody Jinks and Sturgill Simpson, and coming to the cursory conclusion that folks find those artists appealing just because they’re more traditional, and are hedging their bets in case all of country swings that way so they’ve already got a stake in it? If that’s the situation, then why not just sign a Cody Jinks or Whitey Morgan, who already have an established fan base, been doing it for years, and frankly have better songs? One reason is probably because Cody and Whitey would tell Scott Borchetta to get bent. But the question still remains, why Alex Williams of all people? Why this guy, and right now? A traditional country artist like Alex Williams may be a novelty for a major label like Big Machine, but in the big scary music world, there are others like him, and many that have a head start. But you can’t discount the importance of what label is releasing this album, and where from. It’s always fair to consider music while sizing it up against its peers. And in the peer group of Alex Williams—whether regarding the roster of Big Machine or all of Nashville’s major labels in general—the fact that an artist like Alex Williams, and an album such as Better Than Myself made it past the oligarchs and out to the public is a remarkable feat in itself. It is part of that 10% of good stuff for sure. And Better Than Myself gets a little better later in the record with songs like “Old Tattoo” and “Few Short Miles.” Taken individually, most all of the songs of Better Than Myself are pretty damn good aside from maybe “More Than Survival.” It’s when you get hit with one drinking song after another, and even a song like “Freak Flag” that has been done so damn often that you begin to become wary. I want to see Alex Williams go deeper. Okay, you’ve defied the odds and you’re now on the inside of the machine, calling your own shots, and getting traditional country down the conveyor belt. Now it’s time to take the songwriting to the next level, to challenge yourself, and to not just be that Outlaw guy on Taylor Swift’s label, but that Outlaw guy everyone is talking about no matter what record label’s name is on the binding. Alex Williams is good, just not great. It’s one of those records where you have a lot of critical things to say, but end up with a sum positive. But what Alex Williams has is what a lot of artists in the traditional Outlaw community don’t have: an opportunity. He’s established himself as the real deal, crawled inside the belly of the beast while holding onto his own identity and style. Big Machine has even shown some understanding on how to work Alex Williams as a non radio star, debuting this album via NPR and such. Hopefully in the coming years he can bring it home, expand his songwriting vocabulary a bit, and be the mainstream traditional country artist to represent the throngs of hungry country fans looking for a reason to be hopeful in the future of country music.

Review (NPR) : The perception that down-to-earth plainspokenness is a quintessential quality of country music tends to obscure the fact that exaggeration has long been a choice tool of country music-makers, too. In the hits of this decade — when hip-hop's influence has surfaced not only in country production techniques, but the cadences of vocal deliveries and the postures struck in lyrics and performances — this sometimes takes the form of materialistic swagger (i.e. luring attractive women into a "brand new Chevy with a lift kit" or a "big, black, jacked-up truck" that's "rollin' on 35s." Over time, though, the embellishment of rough behavior and rotten luck in songs ranging from Loretta Lynn's "Fist City" and Johnny Cash's "Busted" to Garth Brooks' "Friends in Low Places" and the Dixie Chicks' "Goodbye Earl" has been a reliable diversion for country audiences, and made their own troubles feel less insurmountable. When one of the underdog protagonists on Alex Williams' debut album, Better Than Myself, is confronted with criticism of his alcohol intake, he spins his stubborn refusal to change into outlandish yarns. "Gonna sell off a couple kidneys, buy a starship, fly that thing out west to San Antone," Williams vows, conveying teasing nonchalance with his baritone twang. "Gonna wrangle them armadillos with a bullwhip, start a polka band, then rock the Alamo." All of that serves to set off the bravado of the hook, which he delivers with considerably more vigor: "Before I go a week without a drink / Well, the day's too long and life's too short / to ride on the wagon, dang." Williams is a long-haired, scruffily bearded singer and songwriter from small-town Indiana, who's plied his trade in Nashville since bailing on Belmont University. He distinguishes himself from stylistically fluid millennial peers by following the old-line outlaw country lineage and its tradition of leathery, knowing tall talk. He signaled his admiration for Willie Nelson by enlisting Nelson's longtime harmonica player, Mickey Raphael, to play a few lonesome licks on his album, and pays permanent, visible tribute to Waylon Jennings with a tattoo of the winged "W" logo on his forearm. (Williams' press bio credits the music of both artists, initially encountered in his grandparents' record collection, with setting him on his course.) Better Than Myself also betrays the influence of a more recent predecessor: Jamey Johnson. It was nearly a decade ago that Johnson emerged from industry frustrations with That Lonesome Song, smuggling sophisticated ruminations under the cover of a menacing ex-con persona. Like Johnson did on that album, Williams' relies on phenomenal performances from a hard-twanging, loose-limbed band — made up of first-call session players in Williams' case — whose licks spill into the transitions between tracks. It's a sign of Williams' self-awareness that he opens his album with the title cut, a song that acknowledges tensions that sometime exist between what a person sings and who he is in real life. "Someone told me not long ago that my songs are better than myself," he reports with wry composure. "That the reckless way I'm livin', it don't match my melodies. That the written words I'm singin', they ain't got no honesty." The idea for the song, he's said, came from the way that his former drummer expressed disappointment in him as their band, Williams & Co., limped toward its end. By expanding on that rebuke, Williams establishes his self-deprecating persona and demonstrates his grasp of how authenticity is actually reckoned in the country world. That can be easy to miss when the country music industry gets hung up, for instance, on the idea that what makes Chris Stapleton the real deal is how insulated his rugged soulfulness is from contemporary pop influences. It matters just as much that Stapleton is so compellingly believable in his role of weathered, wisdom-filled, emotionally tough mountain man. In country music, the aesthetic choices artists make don't stand apart from how fully they're integrated into the personas they embody. Williams sure seems to get that. He's all of 26 years old, and nailing the part of the stoned, admirably stubborn, veteran individualist. He's filled his album with familiar turns of phrase, whittled down and repurposed. His slouching characters trust very little in the world other than experience. His 18-year-old self makes an appearance in the dusty story song "Few Short Miles," idolizing a bar fly more than twice his age, who shares with him a wealth of proverbs and a vintage guitar salvaged from a dumpster. Williams' finest moments are his most easeful ones. In "Can't Get Enough of You," a track whose insouciance is underscored by its gently swinging, Jennings-esque groove, he juxtaposes the unlikelihood of choosing all six winning Powerball numbers with the immediacy of feelings of infatuation. In the spry, loping "Pay No Mind," he conveys disinterest in political and religious rhetoric, further mellowing his vocal attack at the end of particular lines and letting their final words dissolve like smoke in the air. In "Freak Flag," an ambiguous kin to Kacey Musgraves' live-and-let-live number "Follow Your Arrow," he chalks imaginative boasts up to personal quirks. "Give me a spool of thread and I'll make the Golden Gate," he ventures. "You got a bag of rocks, well, I'll pave the interstate." Then comes the equalizing shrug: "People are weird and so am I / Lay it on back; let your freak flag fly." The secret Williams has already learned? How to make the whoppers go down easy.

Review (B-Sides & Badlands) : Alex Williams is hellbent on shaking up the country establishment. In the aftermath of Chris Stapleton‘s watershed performance at the 2015 CMA Awards, with pop juggernaut Justin Timberlake in his corner, colossal shifts have rippled outward - from Stapleton’s continued dominance on the Billboard 200 and Miranda Lambert’s platinum achievement with The Weight of These Wings to such up and comers as Jon Pardi and William Michael Morgan collecting their first No. 1 hits. We still must contend with pop, dance and R&B flooding the format - extended with Sam Hunt’s massive success for “Body Like a Back Road” (now perched just outside the Top 10 at pop radio) - but there are signs consumers are outright exhausted with traditional business models and poor man’s shilling down on Music Row. Williams, for his part, throws caution to the wind with his dusty and lonesome disc of tunes, a revelatory debut album called Better Than Myself, released on Big Machine. The titular track, in which he waxes lyrical about a comment made by a former band member, ignites the record - “I was told not long ago that my songs are better than myself,” he unwraps - and sets a rather somber, self-aware tone to a project mostly encased in gritty defiance. “So, you’re still listening right now / I’d say this song is doing pretty well,” he sings, a sheepish grin curling on his lips. “I don’t see it as stab at anyone, I see it as kind of a new beginning for what I’m doing,” he said of the song (cowritten with Greg Becker), which then became the impetus behind his brand of plucky, bleeding-heart Americana. As much as the evocative 1975 concept album Red Headed Stranger was critical to Willie Nelson’s career (and to Williams’ own transformative years), Better Than Myself places the bar of artistic accomplishment unbelievably high. It’s not nearly as well-sculpted or fine-tuned an endeavor as the former, but make no mistake: Williams’ reflections on really living (“More Than Survival,” co-penned with Marshall Altman), hazy-eyed whiskey-slingin’ (“Week Without a Drink,” cowritten with Brandon Kinneyand Jimmy Yeary) and the sting of lost love (“Old Tattoo,” the first solo cut) wrangle together as the year’s best, most promising arrival. But the glaringly-obvious pinnacle of his talents comes with the second of two solo writes, “Few Short Miles (Bobby’s Song),” which walks the line delicately between hope and sorrow. “I was back to play some gigs in that East Texas town just off the coast / But I noticed something missing, like a piece lost from a puzzle / This time, I wondered where my good friend go,” he observes, an air of disenchantment casting his spirit downward, on a brooding tale about an older friend who passes away from cancer. Mickey Raphael, long-time player for Nelson, showers the song (and many others on the album) with heavenly, smokey harmonica. “I used to play gigs at a seaside trucker bar my cousin owned that was south of Houston in a little town in Sargent. I was 17 or 18, and I met Bobby at one of the gigs I was playing and he was a really inspiring guy,” Williams revealed the story behind the song. “We became really good friends in a short period of time while I was playing down there. I decided to write a song about it. He had cancer for a while, and I didn’t know that until the last few weeks before he passed.” Smoked and soaked in the adept craftsmanship of producer Julian Raymond (Glen Campbell, Jennifer Nettles), Better Than Myself preserves some weighty topical lyricism even when he’s letting (musically) loose on such standouts as the swampy barn-burner “Strange Days” (“right now, it’s just all too much to bear,” he maintains in a hurricane of thumping blues guitar), the gentle sway of “Freak Flag” (another cowrite with Altman) and “Pay No Mind” (Williams, Becker), in which he claims “the only place I’m registered to vote is in an inebriated state,” as he reflects on the infamous 2016 political debates, rabid religiosity and various other schemers and crooks. “When I get together with the good woman of mine, I’m feeling light as a feather in this heavy, hazy times,” he upholds, keeping a level head and some humanity about him. Conversely, he takes a moment to expose this “fucked up generation,” he spits on “Little Too Stoned,” a funk-based number which sees Williams at his most brazenly exasperated. “Yeah, I’m a little too gone to care what you think,” he notes, a slurred mix of alt-rock and outlaw waving mischievously behind him. It might not be a career-defining bow, but Better Than Myself frames Williams as one of today’s most essential storytellers. “I do believe the good outweighs the bad,” he later punctuates. Indeed, good sir.